Jerome Bruner, the esteemed cognitive psychologist (who turned 100 on Oct. 1, 2015) stated in a 1976 Psychology Today article: “Play is the serious business of childhood.”1 And ever since, child advocates, educators, developmental specialists—even Mr. Rogers—often echoed Bruner. Why? Because he’s right.

Since 1976 there have been hundreds of studies demonstrating the serious power of play. Youngsters learn critical thinking skills and spatial relationships when digging in the dirt; they learn about who they are when dressing up, pretending to be someone else. When directing their own play experiences, they practice self-regulation and autonomous motivation.

Peter Gray, who has researched play extensively, purports that the decline of free play can be linked to the rise in anxiety and depression. We also know that when children play longer before entering formal schooling, they do much better academically. In Singapore, Shanghai and Finland, three of the highest-performing education systems according to the major international ratings, the average starting age was almost seven years old.

A researched backed 2015 initiative, the Genius of Play reminds parents of play’s many benefits for both optimal cognitive and emotional/social development.

Yet, allowing youngsters free-floating frivolity in our digital age is complicated. In today’s high-tech world, the “glass slab,”2 has entered the child’s world, often interfering with the concept of play Bruner had in mind.

Parents increasingly ask me such questions as:

- How much screen technology should I allow my two- year-old?

- Should five-year-olds have their own I-Pads?

- Should I potty train with an I-Pad?

- Does it harm my nine-month-old to play with my I-Phone when I am too busy to entertain him?

While there are no one-size-fits-all answers to these questions, I believe understanding the young brain’s need for various forms of play can help parents make good decisions about how much screen play to allow.

I advocate this bottom-line brain-compatible guideline for parents of young children:

Provide more opportunities for physical and imaginative play than for screen play.

I know. I know…much easier said than done. So let’s consider each type of play along with some nuts and bolts, nitty gritty practical activities you can do when in the throes of a stressful day with a tired toddler or a petulant preschooler.

3 Types of Play

- Physical play involving movement and sensory experiences.

- Imaginative play involving generative creativity, visioning, and self-understanding.

- Screen play—the play youngsters do on hand-held electronics and computers.

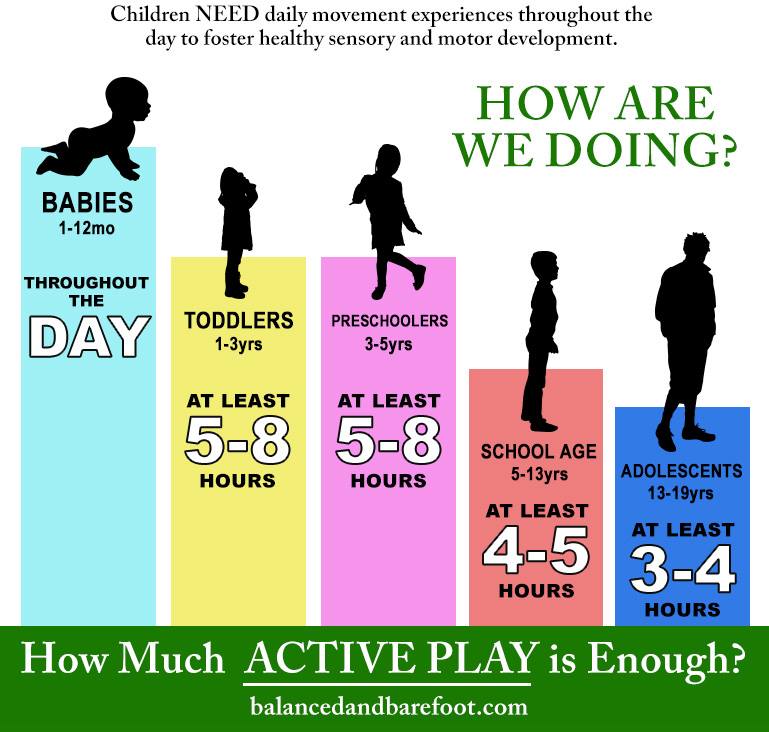

Physical Play: Brains Need Bodies that Move

When babies and young children are moving and exploring their three-dimensional world, they are busy building neural structures in their brains that are the very foundation for all future learning. Movement is absolutely necessary in the early years to grow vital neural pathways for emotional health, social competence, and cognitive abilities.

Dr. Marian Diamond, over a series of experiments spanning more than a decade at the University of California, demonstrated that neurons in the brain’s cortex become larger, growing more complex networks with movement and sensory experiences.3

Other studies show that rats deprived of movement had underdeveloped medial frontal lobes—the brain centers responsible for regulating emotions—demonstrating aggressive and anti-social behaviors when placed in cages with other rats. In contrast, rats raised with opportunities for motor activity had particularly advanced medial frontal lobes. These rats showed greater emotional control and more playful, pro-social interactions with others.4

We are sensory beings, continually processing sensory data, learning from and adjusting our environment simultaneously. In her book Wisdom and the Senses, Joan Erickson points out, “The sorting of incoming sensory stimuli demands concentration and a capacity for quick and fluid evaluation.”5 Without the opportunity to process the complex texturing of sensory data, young brains cannot easily grow selective attention and concentration abilities. Youngsters need to be immersed in the sensory world of concrete, tangible 3-D objects, moving, touching, etc. If you ever tried to keep a puppy perfectly still, you know the frustration (and fruitlessness) of trying to tame the impulse to move—a biological imperative—in young mammals.

We are seeing a sharp rise in sensory-related issues, along with poor motor control in the later years. To prevent or minimize these issues, provide loads of movement and sensory-related activities in the early years. You won’t be sorry you did.

Moving Outside and Inside

The value of playing outside in nature can’t be overestimated. Many studies indicate that experiences in nature build cognitive capacities par excellence. Research from Spain, for instance, shows that time spent climbing trees and playing games on grass, enhance mental functions.

Kids love to roam. Just ask the second graders at Charles R. Drew Charter School in Atlanta who designed and created their own playground. They have no idea that the physical act of climbing a play structure creates a multi-dimensional mental model of the experience inside their heads, furthering their ability to use past memories to learn and rehearse new skills. All they know is they are having fun, and that’s enough!

Rainy Day?

Let youngsters dance or march to some tunes. Research has shown music increases the brain’s capacity by increasing the strength of connections among its neurons. Chimes, bells, triangles, tambourines and other simple instruments enable children to make music as they move. Parents can also turn on an MP3 player and encourage dancing, prancing, marching, clapping, and arm movements with scarves, knowing that they are not only helping their child increase physical fitness, but also nourishing the child’s brain as well.

Fine motor skills such as drawing and painting are important to encourage during this stage of neuro-development. Art activities provide a wide variety of textures, colors, and sensations for the child to experience and integrate. Painting with watercolors, drawing with a fat crayon, and molding clay are all art activities, but they are all different experiences for the young brain, too. New brain cells grow with such enriching activities.

Jean Van’t Hul’s, Artful Parent blog offers magnificent art activities for youngsters.

Imaginative Play

Pretend play is the way young children practice turning internal images into actions. By taking on different roles, for instance, they absorb various image-sets of feelings, attitudes, and actions. When children play, they enter the realm of the imaginal, the world of the artist and poet. This world is their home. It’s where the young mind must hang out if it’s to grow appropriately. Through play experiences, children plan and organize, predict and anticipate, take risks, reflect and experiment..

Decades of empirical research have established the multiple benefits of children’s imaginative play. Because image making forms the basis for thought and because the young brain naturally seeks symbolic experiences, play develops cognitive, emotional, and social learning. Research has found that it also “fosters an impressive array of skills that are necessary for school success including taking another’s perspective, regulating one’s emotions, taking turns with peers, sequencing the order of events, and recognizing one’s independence from others.” 6 Not surprisingly, children who engage regularly in imaginative play are more creative than their peers and often leaders in their peer group.7

It can help to support children’s image-making abilities by reading to them extensively and to providing many opportunities to listen to audio stories. Often children need some help developing their imaginations, before they self-select imaginative play experiences.

What To Say To Help Develop Young Children’s Imagination

“Wow! Your drawing shows you paid attention to your pictures in your head.”

“Before I read another page in the book, let’s talk for a few minutes about any pictures you are seeing in your head.”

“Is what you see in your head the same as this picture in the book? Describe for me what you see in your head.”

“Your brain certainly knows how to be imaginative. Look at the puzzle you put together (the art project you finished, the puppet play you did, etc.).”

“We will read one book about cats with pictures and another book about cats without pictures. Then you can draw your own pictures of cats, OK?”

(For more ideas on helping youngsters develop imaginative play, please see my book, Parenting Well in a Media Age.)

Screen Play

We could debate the word “play” used in various screen activities, because often screen time is not free-form, and not technically “play.” Children are constrained by the choices of the app developer or software writer. If screen-based activities are multiple choice or don’t allow the child to actually create something, their value diminishes for young brains.

Let’s face it; we call them “educational apps” for the basic reason that they are teaching kids something. For instance, Daniel Tiger’s Day and Night is a well-rated app that teaches about daily routines. Children help “Daniel get ready for school in the morning and for bed at night through imaginative play and songs.” But whose imaginative play and songs? We want to be sure to make up original songs, too!

The app, Explore Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, encourages children to make up stories. Advertised as a “digital dollhouse,” it engages the child’s imagination and allows for exploration. Apps that support children’s artistic and creative abilities allow for expressing and tinkering in the digital environment. Common Sense Media has a list of creative apps here.

In determining what types of screen play for your child, you couldn’t go wrong with assessing the app or game with these three simple questions:

- Is it engaging and energizing rather than rote and draining?

- Does it make my child more curious about life?

- Does it promote a sense of play and freedom to learn, rather than being restrictive and controlling?

Ultimately play is all about a sense of fun, freedom, and life. As Bernie DeKovan states in his book, A Playful Path, “…playfulness will lead us back to life itself. All of life.”8

Parting Words

I know video game and Internet addiction is real. I know this from the research. More importantly, I know this first-hand from the many families I have worked with whose lives were negatively impacted by screen addiction and in some cases, whose lives were utterly destroyed.

So, for me, it is a moral imperative to let parents of young children know that the earlier they start with screen technologies, the more difficult it is to use screen technologies age-appropriately. In fact, I am becoming convinced, along with my colleagues, like Dr. Richard Freed, that balance with screen technologies is impossible, especially in early childhood.

I am sure you know this first-hand. You give your youngster time on the I-pad and he nags and whines for more time on the I-pad. You give her your cell phone once to prevent a tantrum in the checkout line, and she’s screaming for it everyday. The incessant desire for the small screen is something adults have problems taming—imagine how difficult it is for young brains?

The irony is that youngsters, who begin early with screen play, are less likely to be able to manage screen technologies when they get older.

So with these realities in mind, I offer my recommendations for allotting time in each type of play:

For toddlers through age 2:

Movement and sensory experiences 85% of child’s play

Imaginative Play 15%

Screen Play 0%

For Children ages, 3-5:

Movement and sensory experiences 70% of child’s play

Imaginative Play 25%

Screen Play 5%

For Children ages 6-8:

Movement and sensory experiences 65% of child’s play

Imaginative Play 25%

Screen Play 10%

References

- “Play is Serious Business,” Psychology Today, March 1976, pp. 126-135.

- David Rose, Enchanted Objects, Scribner, 2014, p. 17.

- Jane M. Healy, Ph.D., Endangered Minds: Why Our Children Don’t Think, Simon and Schuster, 1990, pp. 47-65

- Ibid.

- Joan M. Erikson, Wisdom and the Senses: The Way of Creativity, W.W. Norton and Company, 1988 p. 41.

- Dorothy G. Singer, Jerome L. Singer, Sharon L. Plaskon, and Amanda E. Schweder, “A Role for Play in the Preschool Curriculum,” in All Work and No Play: How Educational Reforms are Harming Our Preschoolers, edited by Sharna Olfman, (Westport: Prager Publishers, 2003) 44.

- Ibid, 63.

- Bernie DeKovan, The Playful Path, ETC Press, 2014.